Raising our Voices

Refugees share their stories of courage and resilience

They fled war.

They escaped persecution.

They fought for their safety.

Now they’re raising their voices for others.

Here are the eight extraordinary people nominated for the Les Murray Award for Refugee Recognition.

In honour of the late Les Murray AM, a former refugee from Hungary who became known as SBS’s ‘Mr Football’, the award celebrates the achievements of former refugees in fields such as arts, sports, media and advocacy.

Asif Sultani

Afghanistan - Iran - Australia

“We may have lost everything we once knew but we have not lost the ability to achieve greatness.”

There are now more than 100 million displaced people around the world and I am just one of them.

I lived in Afghanistan until I was seven years old. My family and I are an ethnic minority called Hazara and, because of this, we were persecuted. This persecution, alongside the war and conflict in Afghanistan, made it very unsafe for me. When I was seven, my family and I fled to Iran with only one bag between us.

In Iran, I was not only persecuted for being Hazara, but also for being an asylum seeker. I used to get bullied, punched, kicked and spat on. To protect myself, I took up martial arts, but after a few months of training, I was told that I was no longer able to attend the dojo because I was an asylum seeker. This broke my heart. I felt like my dream of becoming a successful martial artist could never come true.

A few weeks passed and I realised that if only I can create my dream, then only I can crush it. I gathered some friends and we started training in my backyard, coached by Bruce Lee movies.

When I was 16, I was deported back to Afghanistan alone. My mother came to visit me in the cell, to say goodbye. Unfortunately, I never got the chance to say goodbye to my father. He was never allowed to visit me in the cell and he passed away shortly after I arrived in Australia. To this day, I wish I had the chance to at least say goodbye.

Shortly after arriving back in Afghanistan, I fled to Australia by boat. The boat trip was extremely traumatic and about half-way through the voyage the engine stopped working. I thought I may have reached the end of my journey. But fortunately, after a few hours, the engine started working again and I made it to Australia. When I arrived, I immediately touched the ground to make sure I wasn’t dreaming. All I had ever known was war and persecution, but for the first time in my life I felt safe.

In Australia, I began high school. Having never had an education before, and being much older than the other students, it was difficult. But I made some great friends and I even met my high school sweetheart, now my wife – Grace. Outside school, I continued to train in martial arts. I didn’t have a car or licence, so I used to run to the dojo before and after school. All up, I ran about 20km per day to train.

A year after graduating from high school, I became the first ever refugee from Australia to be awarded an International Olympic Committee Scholarship for the Tokyo Olympics. I hoped to compete in karate for he Refugee Olympic Team, representing millions of displaced people around the world. Unfortunately, after years of training and sacrifice, I was not selected as part of the team. Hearing this news shattered my heart. But that’s okay. Life does not always go according to our plan.

From then on I made a commitment to never stop fighting and raising awareness for refugees and displaced people. This was my original goal and I was determined to find a new way to achieve it. Now I work as a motivational speaker, sharing my story of survival and resilience through my business, Heart Empire. My voice is now stronger than ever and I constantly remind myself that, as refugees, we may have lost everything we once knew but we have not lost the ability to achieve greatness.

Hamed Allahyari

Iran - Australia

“At first, I did it by myself. But then I started employing my friends who also came by boat. I wanted to give job opportunities to people stuck at home with nothing to do.”

I was only able to say goodbye to my mother and father after I’d fled my home country of Iran and arrived in Indonesia. I had escaped with my girlfriend, pretending we were tourists. When we got to Indonesia, I called my parents to say I was going to find an opportunity for a better life. My mum was in tears, asking why I hadn’t said goodbye. That was ten years ago now and I haven’t seen her since.

A few days earlier, some people had come to my restaurant to arrest me. I knew that if I went with them, they would either lock me up forever or hang me. Unknown to my girlfriend and family, I had become an atheist and joined a group which was against the Iranian government. Fortunately, I was able to convince the people trying to arrest me to have a meeting the following week instead.

In Indonesia, my girlfriend and I boarded an overcrowded fishing boat destined for Christmas Island. I told her: “I feel it would be better to be killed by a shark in this ocean, rather than by the Iranian government.” But I also said to her: “You have the option to stay.” She told me if she was going to die, it had better be with me.

The captain of that boat was a very young boy, only 13 or 14 years old. We thought it was crazy that he was put in charge, but he was so experienced.

It was my mother who taught me to cook and that has shaped my life. I loved watching her as a child and, to me, it always seemed like she effortlessly did great and surprising things. Even little things, like putting orange zest in a cake, would excite me.

When I was 19 and moved out with friends, I offered to cook in exchange for not paying the rent. I would call my mum and she would explain the dishes to me, step by step, always with her own creative tips. I became the head of the kitchen at a modern restaurant in Tehran and then opened my own café.

But when I finally got permission to work in Australia, I went to 50 or 60 restaurants and the only job I was offered paid $8 an hour. Instead, I volunteered at an asylum seeker charity. It was during that time I discovered many people in Australia hadn’t tried Persian food and I decided that was going to be my future.

I began teaching cooking classes at a not-for-profit organisation supporting asylum seekers and refugees. People also started to get to know me through Instagram, and would ask about catering and home cooking classes.

At first, I did it by myself. But then I started employing my friends who also came by boat. I wanted to give job opportunities to people stuck at home with nothing to do. They’d say: “I don’t know how to speak English. It’s hard for me. I don’t know anyone.”

People then began asking if there was a place they could come to eat, so I started Salamatea House and we now have about 14 people working there. It’s a not-for-profit because I don’t want to do business for myself – I just want to give job opportunities.

I’ve seen big changes in the people who have worked for me. I have seen them become part of the community, become successful in their lives, and find careers beyond the cafe. They’ve come to life.

Maryam Zahid

Afghanistan - Pakistan - Australia

“Part of what we do is use art – whether it’s plays, talks or visual arts – to celebrate the female refugee experience and change narratives in Australian society.”

The thing that struck me on the way to Australia was how women didn’t need male guardians with them. I first saw it as I stepped into the airport at Kuala Lumpur. So many women who were free to be women, to be human beings. It was just amazing that women could be by themselves, dress or speak how they liked, and not be scared of being killed, or beaten or humiliated.

I have mixed feelings about my childhood in Afghanistan. I co-parented my six younger siblings and wasn’t able to finish a whole year of school. But there is that saying: “Ignorance is bliss.” When you don’t know about other worlds, and if you feel safe and loved, then you feel happy.

It wasn’t until I was 15 or 16 that war broke out. Both my parents, as well as aunties and uncles, were working in government positions or had political affiliations. It was no longer safe for them. We began moving between houses and eventually fled to Pakistan.

With the help of UNHCR, I came to Australia with three of my younger siblings. But we came without my parents. We were quite a large family and my mum and dad were going back and forth to Afghanistan to look after other relatives.

When we arrived, my siblings were easily accepted at school, but I was 20 years old and had to enrol in TAFE instead. Everyone around me seemed much older and it didn’t feel right to me. I thought: “If there is the freedom that they say there is here, then why can’t I capture some of the missed moments from childhood?” School was one of those things. I walked into a high school and persuaded them, in my broken English, to allow me to begin studying there.

At that time, I began getting a lot of counselling because of the trauma I was dealing with. I was so broken – mentally, emotionally and physically. That was how I learned about the importance of community work, of being a good listener and giving people the right information. I’d make note of the job titles of the kind people who were helping me, and they inspired me to go into the community sector myself.

Afghan Women on the Move was partly born out of the gaps I saw in the system, and partly out of my own loneliness. I was sure there would be other women in Australia, some who had been here for decades, who didn’t feel a sense of belonging.

What began as an online support group for women has now become a movement. I have seen how it has created momentum in our community and is now encouraging and inspiring women from other

backgrounds as well.

Part of what we do is use art – whether it’s plays, talks or visual arts – to celebrate the female refugee experience and change narratives in Australian society. I am a playwright and one of my plays, The Good Woman, is about challenging the perceptions of how multicultural women are allowed to behave in contemporary society and showing that we can speak for ourselves.

Refugees are sometimes painted with the same brush. People think we came here just to be safe and have food. They sometimes don’t realise we probably had a good life once and that we came here with eagerness, with passion and with love. We also know the value of loss – that things can be taken away in a matter of a minute.

I’m fighting for justice. If opportunities were given equally to all, everything would be better.

Danijel Malbasa

Yugoslavia - Croatia - Serbia - Australia

Winner of the Les Murray Award for

Refugee Recognition 2022

“Refugees contribute so much more than we cost. Our stories, our lives, shouldn’t be controversial. We need to hear the stories of success.”

I come from a country that no longer exists. The first time I became a refugee was in 1993 during the Croatian War of Independence. It was a very brutal civil war. We’re talking neighbours killing neighbours, cousins killing cousins.

The second time was during the Kosovo War. I spent my childhood going from one war zone to another, transiting through refugee camps in Eastern Europe, working as a child labourer to survive.

We ended up living in a refugee camp on the outskirts of Kosovo. It was a large sewing factory. They removed the sewing machines and put down mattresses on the floor. That’s where we lived for about five years with 800 people sharing one bathroom and one hot plate. It was a really difficult situation.

We were lucky that there was an Australian Embassy in Belgrade. My mother put in an application to get as far away from Europe as possible. I didn’t know anything about Australian culture – just Blinky Bill, the anthropomorphic koala.

I resettled in Adelaide in 1999 with my mother, my twin brother and an older brother. I was 12 and didn’t speak any English. After some initial difficulties in adjusting to a new culture, we thrived in Australia.

After school, I began a journalism degree. I wanted to be Christiane Amanpour. Then I went to a model UN conference in Sydney, and I was impressed by how the law students got up and spoke about international conventions and treaties, about war crimes and crimes against humanity – about things I lived through, but they only understood in the narrow abstract. Upon my return to Adelaide, I enrolled at Adelaide Law School. I wanted to use the law to contribute to causes I care about.

Now, I practise employment law and industrial relations for a large blue-collar union. I have stuck with law for almost 13 years now, and I really love it. In my line of work, we get to set precedent for employment law in this country. To develop case law and legislative amendments through our law reform work – this is exciting for me.

Coming into daily contact with people who had never met refugees, but had negative views about them, made me reflect on my experience as a child refugee. I started telling my story to educate the Australian public about the issues refugees face. I’ve had my writing published in The Guardian and The Age and in three books, including New Humans of Australia. I’m also the Deputy Chair of the Forcibly Displaced People Network – Australia’s first LGBTIQ+ refugee network – and I sit on the steering committee of the National Refugee-led Advocacy and Advisory Group.

For a long time, I didn’t want to be labelled as a refugee. I used to wish I could advocate for refugees anonymously, from the shadows – like an advocate version of Sia. With my back to the audience. A mask concealing my face.

I felt that way because the perception people have of refugees is of depravity and risk. Refugees are seen as a burden. I was not a burden. I was a 12-year-old child in need of protection. I want to change that perception.

Refugees contribute so much more than we cost. Our stories, our lives, shouldn’t be controversial. We need to hear the stories of success. That’s why I’m speaking up – to own this space for us.

Forcibly Displaced People Network

Forcibly Displaced People Network (FDPN) is the first organisation in Australia to dedicate its work to the issues of LGBTIQ+ forced displacement and be driven by the lived experience of it. FDPN promotes human rights and inclusion of LGBTIQ+ persons in forced displacement through peer support and strengthening services and policy responses.

National Refugee-led Advisory and Advocacy Group

The National Refugee-led Advisory and Advocacy Group (NRAAG) is a refugee-led entity that aims to create spaces, platforms and strong voices led by former refugees, people from refugee-like backgrounds, and people seeking asylum.

NRAAG aims to inform key policies, service delivery, campaigns, research and key initiatives affecting the lives of its constituents with a range of partners and allies.

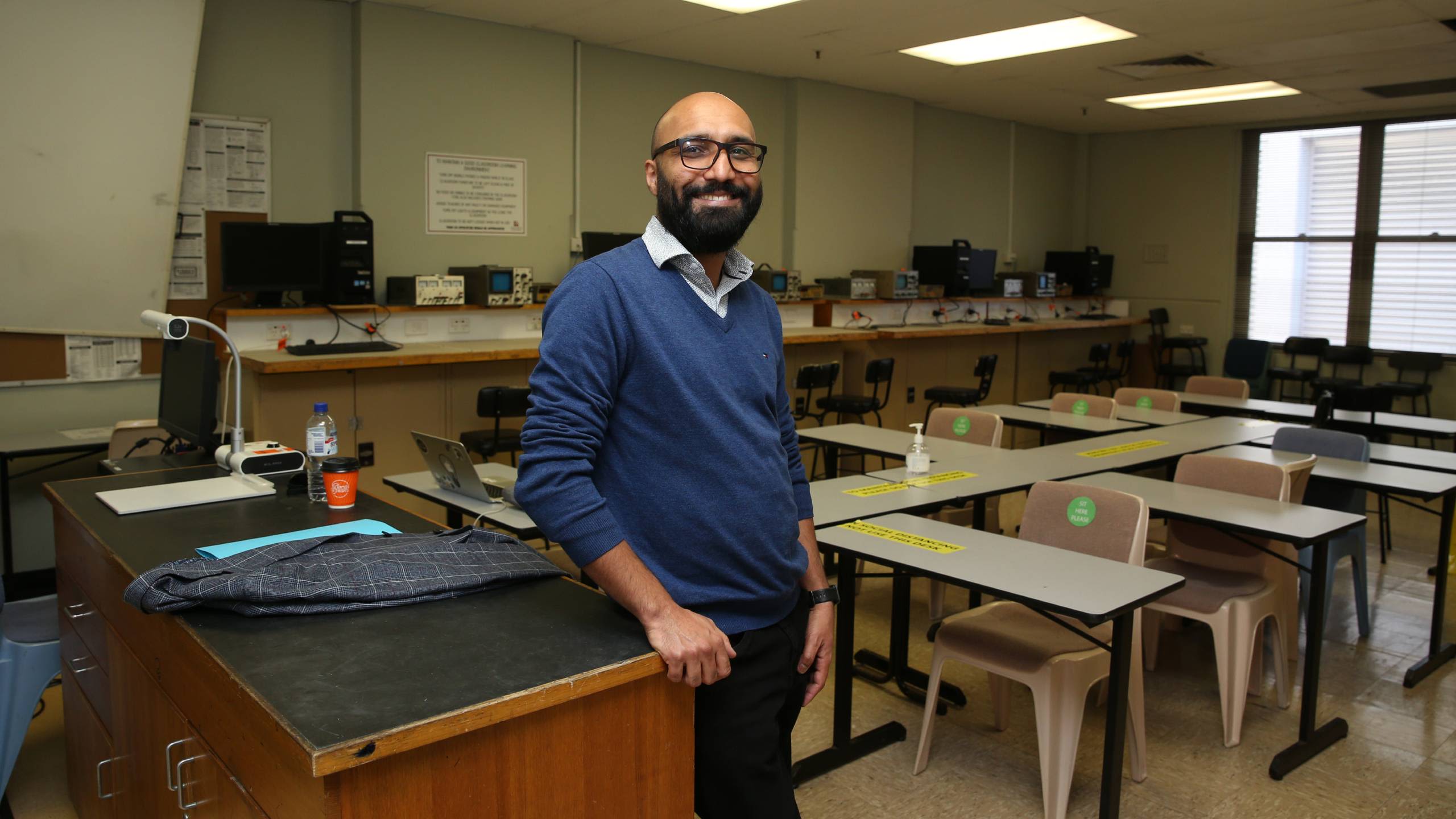

Mohsen Joyan

Afghanistan - Iran - Australia

“The system would work so much better in Australia if we gave refugees more motivation, encouragement and inspiration.”

When I was a teenager I wondered why the world was so cruel that it didn’t just let me get an education. That was the biggest source of my pain. I wanted to study, but it was such a struggle to do so.

I am from Afghanistan, but I grew up as a refugee in Iran. At that time, it wasn’t easy for refugees to go to school. There were so many restrictions, people simply gave up. But my family was determined and fought really hard to get special permission for me to attend school. I later built on that education in both Afghanistan and Australia.

We moved back to Afghanistan when I was in my twenties, living close to the border in case we had to make a quick escape. I began to feel something I had been missing my entire life – a sense of belonging, of finally having an identity. I never felt that in Iran and, even though there were security concerns in Afghanistan, I felt wonderful – like I was having the time of my life.

I moved to Australia in 2008. People told me that in Australia there was every kind of support you could imagine. You just name it and they will grant it to you. Like having a genie in a bottle. But when I couldn’t find a job in my field of telecommunications, all my hopes and expectations crashed down. I felt like I was wasting my life. I told my brother I wanted to come back to Afghanistan because, even though there were dangers, at least I had self-respect.

Many migrants and refugees accepted that this was just the way it was, but I had to believe that I could find a way. In the end, I got lucky. A big 4G rollout project started and there was a high demand for workers. That first shift I was expecting everything to be really different, but when I started I thought: “It’s all the same! Exactly the same equipment and same processes.” I was promoted to team leader within four weeks.

I eventually started my own business and, when I started recruiting workers myself, I realised there was a huge gap between what businesses needed and the expectations of employees from refugee and migrant backgrounds.

I started an online directory, but connecting refugees and employers was just one side of the story. Now we are working on a training and education program designed to ease the transition into the workforce.

The idea of changing the world really inspires me, but it has to be in a way that is sustainable and I believe education is fundamental to that. To me, education is more than just reciting information and receiving a piece of paper to say you have graduated. It’s about really being made to think.

The system would work so much better in Australia if we gave refugees more motivation, encouragement and inspiration. These are usually people who have gone through hell to get here and are pretty ambitious. We just need to make sure they don’t get stuck in the system.

I now have three children and I have a sense that they are going to have a bright future. But I’m also trying to teach them not to take it for granted. They need to be really appreciative and live life to the fullest.

Yasmeen Ahmed

Myanmar (Burma) - Malaysia - Australia

“I am passionate about inspiring young Rohingya girls to pursue careers and break cultural stigmas.”

My childhood was spent in a country where we never really belonged. I was born in Rakhine State in what was then Burma, but my family fled to Malaysia when I was very young. The persecution facing Rohingya people in Myanmar today has existed for a long time and we now have relatives in every part of the world because they also fled.

My family’s journey from Burma to Malaysia was very dangerous. We passed through multiple countries, walking most of the way. We were tired, hungry and terrified. Fortunately, I didn’t have to live in the refugee camps like Rohingya people do now, but we faced other challenges once we reached Malaysia.

We couldn’t get citizenship or even permanent residency. So, for many years, we had to live as illegal immigrants, always moving, to prevent police and immigration from catching up with us. My siblings and I were living only to survive. We were very different from the other children in Malaysia, who could live without fear and enjoy their lives.

We had escaped our country, but we were still searching for a place to belong. If you don’t have documents, you don’t have a future. That’s why we came to Australia.

UNHCR helped us with supporting documents which allowed us to get out of Malaysia. I was around 19 when we arrived. It really was a new chapter, a new beginning. The worry that we would be arrested lifted straight away. It was just wonderful.

My siblings and I were accepted into high school and completed our HSC. Now I am a high school teacher myself. I also work at SBS Rohingya. For me it’s about keeping our language alive and introducing our stories to Australia. It’s also a very important way for our community to feel like they belong and their voice is heard.

I’ve been very active in helping refugees in other ways too, whether that’s as a cultural support person helping my fellow Rohingya navigate the public health system, or as part of the Rohingya Women Network group. I am passionate about inspiring young Rohingya girls to pursue careers and break cultural stigmas.

I also have a dream of doing more to help refugee women living in Bangladesh, particularly with education. I would love to dedicate time weekly, or even daily, to provide lessons online. I believe that if we can educate women we can educate the whole family.

My desire to help is probably born out of the fact that I missed a lot of things in my own childhood. I want to prevent other people from missing out as well. There also wasn’t much support available back then, so I stood up and thought: “I should be the person to inform them because I don’t see many other people wanting to do it.”

When I hear about terrible situations in other countries, I feel sad. I think: “Once upon a time, I was in their position.” Maybe it wasn’t as severe, but I can still relate. I was running in search of a place that I could call home, but these people are running to find safety in their own country.

I’m waiting for the day there will be peace in this world, but I don’t know when it’s going to happen.

Hangama Obaidullah

Afghanistan - Pakistan - Australia

“I have seen how my story can encourage and inspire people, especially women, to value themselves and be more ambitious and courageous about their own future.”

I was in primary school when the Taliban first took control of Afghanistan. It was devastating for my mother. She had struggled so much as a single mother to give us a better life, and wanted her children to graduate from university.

She always said to us: “If you have knowledge, you will be okay. You can lose your money, your home, your position, everything you know, but with knowledge you will find your way.” I have lots of sad memories from my childhood, but I was very lucky to have my mother. I clearly remember the day she gave me a full set of coloured pencils. I was about 11 years old and it marked the beginning of my love for art.

She died when she was only 41. It was then I realised I didn’t want to live in Afghanistan anymore. I was born and raised in a society where women have few rights and are regular victims of violence. I experienced war, limited education and few freedoms. It is hard for women to be confident in these conditions, but the idea of leaving behind our home and all our belongings isn’t easy either.

A miracle changed my life forever. When my mother died, we were in Pakistan and one of the nurses caring for her was Australian. I had never heard of Australia before I met Jan, but I always had this belief there was another world which would be safe for me to live in. A place where I could live peacefully and achieve my goals.

Jan and her husband, Martyn, are the reason my two sisters, brother and I came to Australia as refugees. I will never forget the smiles on the faces of Jan and her family when I met them at Sydney airport in 2003. The only things I could say in English were “hello” and “thank you”.

That first night here, I was so relaxed and had the sweetest dreams. I felt like I had found myself. And, finally, I felt safe.

I had a very strong urge to learn all about this new society I was living in. I enrolled to learn English and loved being back in the classroom after so long. I didn’t feel like a young woman, but like a child going back to school. It felt beautiful.

I saw my art as a way of connecting with the community, of no longer feeling alone. My artworks are inspired by my culture and I wanted to tell my new country why I came here: not because I wanted a luxury life, but because I wanted to be safe. I also wanted to say: “I am a human and I exist in this world. And I have something; I have an idea and I have a passion.”

My paintings and photographs have been exhibited in both Australia and overseas, and I have published and performed my writing and poetry to raise awareness of the refugee experience as well as the history and culture of Afghanistan.

I have seen how my story can encourage and inspire people, especially women, to value themselves and be more ambitious and courageous about their own future. I support them to build their skills, confidence and social networks through regular art workshops and other programs.

When I first heard that Kabul had fallen to the Taliban again, I was sick for a week and couldn’t stop crying. It reminded me of my childhood and what my siblings, and my mother, had suffered. Humans deserve to live a peaceful life.

Reza Rostami

Iran - Australia

“We still don’t have any certainty whether we will get permission to stay here permanently. That’s the trauma we continue to face today. It’s a limbo that affects mental and physical health.”

Two hours before we reached Christmas Island by boat, my youngest daughter stopped breathing. She was 18 months old and hadn’t eaten in four days and four nights.

My wife and I, along with our two daughters, had boarded the boat in Indonesia, less than a week after fleeing our home country of Iran. I didn’t know anything about Australia or how we’d get there. We travelled to Indonesia on fake passports and, when the people smuggler there told us to prepare for the boat trip, I asked if there was any other option. It seemed a long way by boat between Australia and Indonesia, but he told me that was the only way.

As my daughter began turning blue, other people on the boat leapt into action. They performed CPR on her small body and, fortunately, she began to breathe again.

There are different stages of trauma an asylum seeker goes through. That boat trip was the second trauma I faced. The first was fearing the government in Iran.

I had been working as a mental health scholar for the government when I was called in, twice, to speak with Tehran’s intelligence service about my attitude and opinions. I was scared for my family’s safety. We knew we had to get out.

When we finally arrived on Christmas Island in 2013, I felt happy because we’d managed to escape Iran without being caught or hurt. But I was also shocked because I didn’t know about detention centres. That was the next trauma – finding out that the reality of the place we’d sought safety in was very different from what we had imagined.

After a couple of years living in various types of detention, I was given a temporary visa without work or education rights. We still don’t have any certainty whether we will get permission to stay here permanently. That’s the trauma we continue to face today. It’s a limbo that affects my mental and physical health.

I didn’t want to lose the knowledge I had from Iran. I wanted to improve myself. Every day I was in detention, I spoke to other asylum seekers about their experiences and learned from them. I later did cash-in-hand jobs, from painting to restaurant work, to pay for more education in my field. Among my studies, I completed a Master of Research at the University of NSW’s School of Psychiatry.

Now, as a research officer at UNSW, I’ve been able to look in depth at mental health impacts on asylum seekers and refugees. My Master’s research examined how the asylum seeker process affects children who remain with their families. It showed how children living with the insecurity of bridging visas for up to seven years experienced almost double the rates of psychosocial difficulties as those with permanent residency.

In coordinating my research with hundreds of families, I also took on an informal role as a community advocate and support worker, helping people build new lives while living with visa insecurity and the subsequent lack of access to services. I was honoured to be announced as the winner of the Refugee Community Worker category in the 2021 NSW Humanitarian Awards.

My family and I are still impacted by insecurity and exclusion to this day. For example, my eldest wants to go to university next year but if she doesn’t get a scholarship we would face expensive international student fees that we can’t afford. I tell her not to worry, that I’ll figure it out somehow. I am optimistic my daughters will have a good life, but it’s still a big challenge for us.

We are still waiting for certainty, but in the meantime we have a responsibility to ourselves, our families and community. Constantly learning and improving ourselves is the way to a better life.